VNS as a treatment for depression

The following is a brief overview of VNS for the treatment of depression. We discuss what VNS involves and cover some of the clinical outcomes reported for this type of treatment.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe vagus nerve

The vagus nerve is the longest of the cranial nerves, deriving its name from the Latin for 'wandering'. It runs from the brain stem through the neck, thorax, and abdomen. It carries signals responsible for controlling smooth muscle in the lungs and gastrointestinal tract, and is responsible for slowing down heart rate.

However, the vagus nerve is not only a parasympathetic efferent nerve. 80% of its fibres are sensory fibres, transmitting information from the body to the brain. These fibres carry information to the brain stem, and on to the forebrain, amygdala, hypothalamus, thalamus, orbitofrontal cortex, and other parts of the limbic system involved in the regulation of mood.

Development of treatment

VNS was postulated as a method of stimulating higher brain activity as early as 1938. The first human VNS implant was performed in 1988 for treatment of epilepsy. Since that time, VNS has become established for treatment-resistant partial onset seizure disorder and by 2004, more than 28,000 epilepsy patients in 24 countries have been treated with VNS.

What does it involve

VNS involves subcutaneous implantation of a pulse generator, of a similar size and in a similar location to a cardiac pacemaker. Bipolar electrodes extend from the device and are wrapped around the left cervical vagus nerve in the neck, near to the carotid artery.

In most cases, the stimulator will be on for 30 seconds every five minutes but the frequency and intensity of the stimulation is controllable using a 'wand' connected to a tablet computer.

Outcomes from VNS for depression

Challenges with the evidence

There are a number of challenges when trying to provide clear outcomes from VNS:

- Duplicate reporting in early studies. Many early studies reported outcomes at one-year and then two-years, often with slightly higher numbers of patients. However, the same patients appear in multiple studies.

- There is only one randomised controlled trial (RCT) which was only 12 weeks in duration (Rush et al, 2002). Since benefits from VNS may take 6-12 months to be evident, this trial was probably too short to be conclusive. Although the two groups (VNS vs sham VNS) did not differ on the primary outcome measure, the VNS group were slightly better on the secondary outcome measure.

- Many patients in earlier studies had bipolar disorder, and/ or they varied in how chronic and severe they were.

- There have not been long-term RCTs comparing VNS with alternatives such as: expert-led psychopharmacology; evidence-based psychological therapies delivered by expert therapists.

Characteristics of patients undergoing VNS

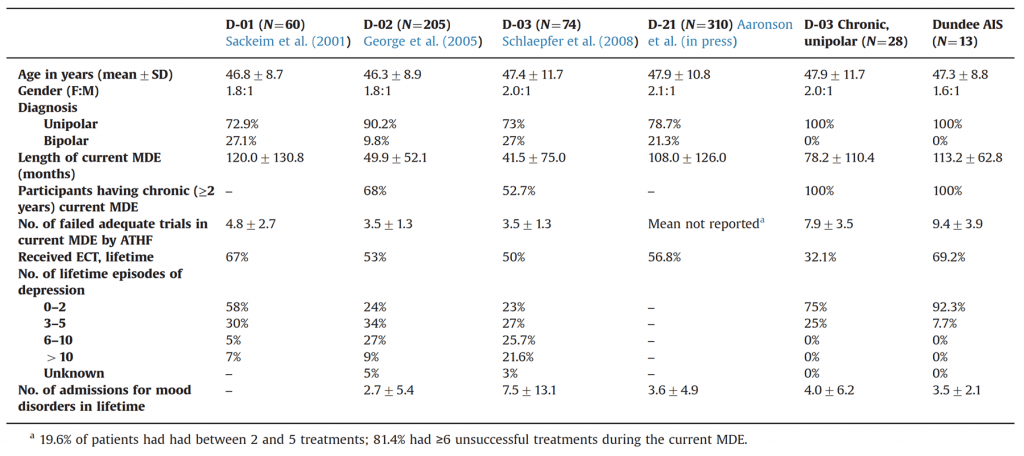

The table below shows the illness characteristics of participants in various VNS studies. The fifth column shows the characteristics of the D-03 chronic depression subgroup, and the final column shows patients treated with VNS in the AIS.

It can be seen that approximately 20-25% of patients in early studies had bipolar disorder, and not all patients had chronic depression (major depression persisting for at least two years).

Randomised controlled trials

As stated above, there are only two RCTs:

- Rush et al, 2002: This was a twelve week randomised period as part of a larger trial (which also included a one-year follow-up period) of VNS.

- Aaronson et al, 2013: Patients were randomised to different 'levels' of VNS (high, medium, and low).

Systematic reviews

Since there are very few RCTs, it is not possible to do proper systematic reviews. Two relatively-recent systematic reviews (based mainly on non-randomised studies) have both reported potential benefits from VNS (Bottomley et al, 2020; Zhang et al, 2020).

Long-term (open) cohort studies

Most studies have reported long-term outcomes from cohorts of patients who have had VNS. All patients know that they have active VNS and there are no active controls.

The results of some of these studies are shown below.

Studies in more severe and chronic populations

Due to the variation in patients in early studies, we undertook to examine outcomes for patients with unipolar (not bipolar) depression who were both severe and chronic. We did this by only including patients who met these criteria from the D-03 study, and we also compared patients who had had VNS implanted in Dundee. Results were as follows:

- Overall response rates at 12-months range from 27% in the D-02 study, to 53% in the D-03 study.

- In the subgroup of D-03 patients with chronic, treatment-refractory unipolar depression, 10/28 (35.7%) met criteria for response at 12-months.

- In the Dundee group of patients, 4/13 (30.8%) of patients met response criteria at 12 months. This means that, within this highly refractory group, response rates are consistent with the published literature.

Adverse effects from VNS

General side effects

VNS is generally well tolerated. Some patients will, however, experience some adverse effects in the early stages of treatment. Almost invariably, these adverse effects are associated with the times that the stimulator is on (30 seconds every 5 minutes). At three months, common side effects include the following:

- Voice alteration (53%)

- Headache (23%)

- Neck pain (17%)

- Cough (13%)

At 12 months, most adverse effects have reduced, with the exception of voice alteration which may still persist in up to 21% of people. Changing the frequency or intensity of stimulation can improve adverse effects, and patients are also given magnets which can temporarily switch off the stimulator when held over the device.

Other side effects

There are isolated reports of cardiac effects of VNS, with asystole occurring in 0.1% of cases when the stimulator is first turned on. No fatalities or long-term sequelae have occurred.

Psychiatric adverse effects are uncommon, although there have been two cases of mania in 30 patients receiving VNS for treatment-refractory depression (Marangell, Rush, George, et al, 2002).

References

AARONSON ST, CARPENTER LL, CONWAY CR, REIMHERR FW, LISANBY SH, SCHWARTZ TL, MORENO FA, DUNNER DL, LESEM MD, THOMPSON PM, HUSAIN M, VINE CJ, BANOV MD, BERNSTEIN LP, LEHMAN RB, BRANNON GE, KEEPERS GA, O'REARDON JP, RUDOLPH RL, BUNKER M. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Therapy Randomized to Different Amounts of Electrical Charge for Treatment-Resistant Depression: Acute and Chronic Effects. Brain Stimulation. 2013; 6(4): 631-640. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2012.09.013

BOTTOMLEY JM, LEREUN C, DIAMANTOPOULOS A, MITCHELL S, GAYNES BN. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) therapy in patients with treatment resistant depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2020; 98: 152156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.152156

CHRISTMAS D, STEELE JD, TOLOMEO S, ELJAMEL MS, MATTHEWS K. Vagus nerve stimulation for chronic major depressive disorder: 12-month outcomes in highly treatment-refractory patients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013; 150(3): 1221-1225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.080

RUSH AJ, MARANGELL LB, SACKEIM HA, GEORGE MS, BRANNAN SK, DAVIS SM, HOWLAND R, KLING MA, RITTBERG BR, BURKE WJ. Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Randomized, Controlled Acute Phase Trial. Biological Psychiatry. 2005; 58(5): 347-354. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.025

MARANGELL LB, RUSH AJ, GEORGE MS, SACKEIM HA, JOHNSON CR, HUSAIN MM, NAHAS Z, LISANBY SH. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for major depressive episodes: one year outcomes. Biological Psychiatry. 2002; 51(4): 280-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01343-9

ZHANG X, QING M-J, RAO Y-H, GUO Y-M. Adjunctive Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression: a Quantitative Analysis. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2020; 91(3): 669-679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09726-5

Image credit: https://www.scientificanimations.com/wiki-images/.

Last Updated on 22 November 2023 by David Christmas